Overview

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) is a common paediatric disorder and affects up to half of babies under two months.1 Although GOR tends to resolve by the time an infant is one-year old, it can have a significant effect on the infant, parents, and NHS resources.1,2

This article explores the signs and symptoms of infant reflux, the impact it has and how to effectively manage infants with reflux in the community.

What are the symptoms of infant reflux?

GOR refers to the effortless regurgitation (often referred to as posseting) of gastric contents into the oesophagus.3 Babies with GOR can regurgitate up to six times a day, often after feeding without experiencing distress.1 They can continue to feed and gain weight well without having any other symptoms.1 These babies are described as ‘happy spitters’ and there is no need for treatment.

Gastrooesophageal reflux disease (GORD) refers to GOR that causes symptoms requiring further investigation and/or treatment.3 Infants with suspected GORD may present with multiple symptoms which include:

- Irritability, excessive crying or crying while feeding1

- Unexplained feeding difficulties; refusing to feed, gagging or choking4

- Faltering growth4

- Hoarseness and/or chronic coughs4

- One episode of pneumonia4

It is possible for infants to experience the above symptoms secondary to silent reflux. This refers to the movement of gastric contents up the oesophagus, but not to the extent that there is visible regurgitation or vomiting.4

When assessing an infant with suspected GOR/GORD, look out for red flag symptoms indicating conditions other than GORD as further specialist investigation may be required.

GORD symptoms include:4

- Frequent and projectile vomiting

- Bilestained vomit

- Haematemesis with the exception of swallowed blood (e.g., following a nosebleed)

- Onset of regurgitation and/or vomiting after 6 months old or persisting after 1 year old

- Blood in stool

- Abdominal distension, abdominal tenderness, or palpable abdominal mass

- Chronic diarrhoea

For an extensive list of symptoms indicating the need for further investigations, refer to the NICE clinical guideline for reflux in children (NG1).4

Frequent vomiting alongside blood in stool and/or chronic diarrhoea can indicate cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA). If this is suspected NICE guidelines for CMPA should be followed.4

The impact of infant reflux

Parental anxiety

Frequent regurgitation can cause agitation and excessive crying in infants, which can have a significant impact on parental quality of life. One study found that the behaviour of infants with frequent regurgitation associated with distress caused maternal feelings of frustration and anger which in turn, severely affected the mother and infant relationship.5 The symptoms of GOR/GORD can be distressing for parents and may trigger perinatal mental health problems. Health care professionals (HCPs) should have a low threshold for questioning and treating mental health concerns in parents of infants presenting with GOR/GORD.6 Parents should be reassured that GOR/GORD is a common occurrence. HCPs can signpost parents to charities (e.g., CRY-SIS) for support in coping with a crying baby.

Parents of infants with suspected GOR/GORD should have access to a health visitor, GP or midwife. Communication with HCPs can help to reduce the risk of parents turning to the internet for medical advice, which can fuel anxiety further. Taking a good history is key to making a diagnosis. Parents should be encouraged to collect relevant information prior to appointments with HCPs (e.g., symptom diaries or videos of their child’s regurgitation) to help build a clinical picture.

It is important for HCPs to provide reassurance that GORD can nearly always be treated alongside continued breastfeeding.6 It is noted that some breastfeeding mothers may lose confidence in feeding infants with GORD secondary to the distress caused during or after feeds.6 Support should be offered to help breastfeeding continue in accordance with the mother’s preferences.6

For more information on effective consultations to support and inform parents and carers (including the use of motivational interviewing), HCPs can visit the SMA reflux management learning module.

NHS Resources

It can be difficult for HCPs to distinguish the small number of infants with GORD who may benefit from treatment, from the much larger cohort of infants with GOR. This clinical challenge can result in repeated HCP visits and an over diagnosis of GORD, leading to secondary care involvement and the over treatment of prescription alginates.6 In 2021-2022, infant alginates were prescribed six times more than feed thickeners and 50 times more than anti-reflux formulas, costing the NHS £4,572,927.7,8,9

At the other end of the spectrum, HCPs may doubt the incidence of GORD, preventing the diagnosis of severe cases, which can again result in repeated HCP visits.6

How to treat infant reflux

Many parents are likely to have made changes to formulas, feeding positions and winding techniques in an attempt to manage infant reflux. It is helpful to discuss with parents the stepped-care approach to GOR/GORD treatment and set expectations for the timeframe of recovery. Parents should be re-assured that reflux in babies resolves without treatment in 90% of infants by the time they are one year old.4

Nutritional management

Positional management for GOR is not recommended in sleeping infants. Infants should always be placed on their back to sleep.4 NICE clinical guidelines state that a breastfeeding assessment is the first-line treatment for breast-fed infants with GOR/GORD. This should be carried out by a HCP with appropriate expertise. The Breastfeeding Network can help mothers access this support.

In formula fed infants with frequent regurgitation associated with marked distress, a stepped care approach is recommended using the following structure:4

- Review the infants feeding history

- Suggest a reduction in feed volumes only if excessive for the infant's weight

- If the infant is consuming large volumes of formula, suggest a trial of smaller, more frequent feeds (while maintaining an appropriate total daily amount of milk)

- Offer a trial of thickened formula for reflux (e.g. SMA® Anti-Reflux)

When recommending thickened formulas, HCPs should advise parents that preparation methods may differ from standard formulas and fast flow teats may be required. It’s important to follow the preparation instructions on the tin

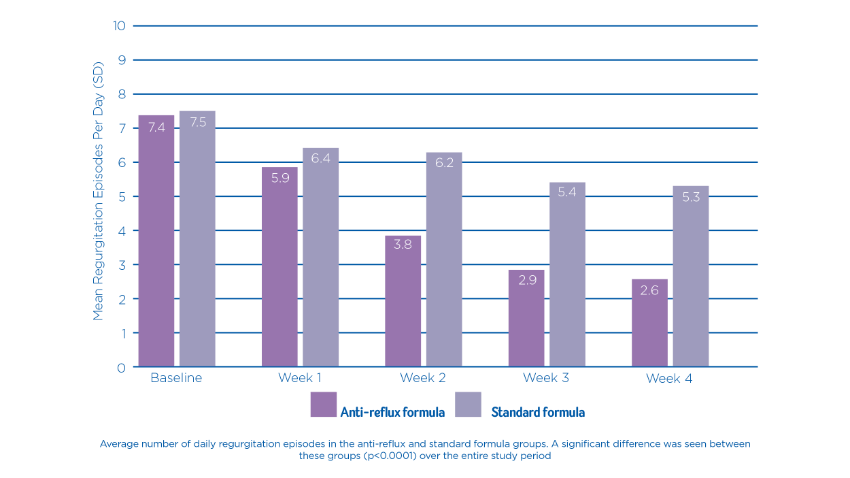

A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial found that a starch-thickened, partially hydrolysed infant formula, led to a significant improvement in regurgitation frequency in infants diagnosed with GOR (as demonstrated in figure 1), in comparison to a standard infant formula.10

Figure 1: Mean number of daily regurgitation episodes by week in the test and control groups10

Alginate Therapy

In breastfed infants, if frequent regurgitation associated with marked distress continues despite a breastfeeding assessment, alginate therapy should be considered for a trial period of one to two weeks. If the alginate therapy is successful, it can continue to be used and stopped at frequent intervals to assess recovery.4

In formula fed infants, if the stepped care approach is unsuccessful, the thickened formula should be stopped, and alginate therapy trialled for one to two weeks. If the alginate therapy is successful it can continue to be used and stopped at frequent intervals to assess recovery.4

For further top tips on how to manage paediatric feeding issues in the community watch this webinar.

Pharmacological Therapy

NICE guidelines state that a four-week trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) can be considered for children and young people with persistent heartburn, retrosternal or epigastric pain. PPIs and H2RAs should not be used to treat overt regurgitation in infants and children occurring as an isolated symptom.4

Response to the trial of the PPI or H2RA should be assessed and a referral to secondary care (for possible endoscopy) should be made if symptoms:4

- do not resolve or

- recur after stopping treatment

NICE guidelines states that metoclopramide, domperidone or erythromycin should not be used to treat GOR/GORD without secondary care involvement.4

Conclusion

Gastro-oesophageal reflux is a common condition in infants which often requires no further treatment other than parental reassurance. It is important that HCPs are able to recognise the signs and symptoms of GOR/GORD and implement the treatment pathway to manage it within the community and avoid unnecessary hospital admissions.