Faltering Growth

Overview

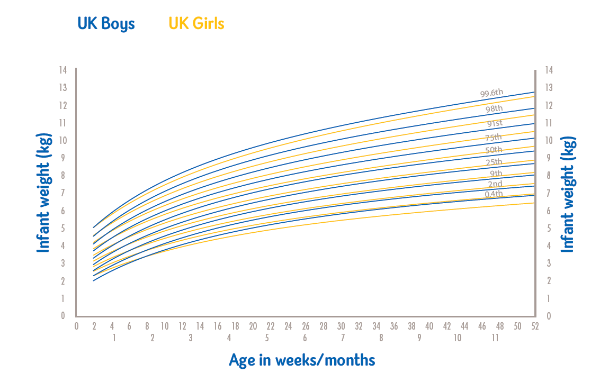

Faltering growth may be caused by inadequate intake due to a variety of feeding and behavioural difficulties, including medical conditions that are associated with increased requirements or malabsorption.1,2 The 2009 UK-World Health Organisation (WHO) growth charts are frequently used to define faltering growth. A sustained drop of weight of two or more centiles is not a normal pattern and requires careful assessment.2,3

This article demonstrates the importance of nutrition in infants and provides in-depth guidance to managing the problem(s).

Faltering growth can be a multifactorial problem

Infancy marks a period of rapid growth in which nutrient requirements (per kg body weight) are proportionally higher than at any other time of life. Young children are more vulnerable to the short- and long-term effects of malnutrition, so early diagnosis and intervention is vital.4

Early growth faltering may have long-term health implications5,6

Faltering growth in early infancy (<8 weeks) has been shown to be associated with persisting deficits in IQ at age 8 years5, and a slower rate of height gain throughout childhood.6 Screening for, and early identification of malnutrition is therefore important to support prompt initiation of nutritional treatment to achieve better outcomes.7

Importance of protein: energy ratio for optimal catch-up growth

Nutritional management in faltering growth cases aims to achieve catch-up growth in order to sustain normal development through improved protein and energy intake and correction of micronutrient deficiencies. WHO guidelines recommend that 8.9-11.5% of energy should be provided as protein to provide optimal catch-up growth.8

Challenges arise as these infants have an increased need for higher calorie intakes but are unable to manage large fluid volumes. Energy dense, low-volume formulae have been developed to address these needs.

Gastrointestinal tolerance of high energy formulas is key

Good gastrointestinal tolerance of high energy formulas is important to maximise nutritional intake. Whey dominant formulas, containing partially hydrolysed protein promote a shorter gastric emptying time making the formula easy to digest.9The UK Department of Health and Irish Health Service Executive also recognises that whey protein is easier to digest.10,11

Breast milk has a unique fat structure that is easy for infants to absorb. This fat structure is commonly referred to as SN-2 palmitate. Formulas containing an SN-2 palmitate enriched fat blend have demonstrated improved fat and calcium absorption, and softer stools in both vulnerable and healthy paediatric populations.12–15

Extra support: HCPs

Full NICE Guidelines on faltering growth: recognition and management https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG

-

Sullivan PB and Goulet O. EJCN (2010) 64, S1.

-

Wright C. Arch Dis Child 2000;82:5–9.

-

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 41, 8–11.The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health UK - WHO growth charts, 2009. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/growth-charts Accessed October 2018.

-

Agostoni C, Axelson I, Colomb V, Goulet O, Koletzko B, Michaelsen KF et al. (2005). JPGN 41, 8–11.

-

Emond A, et al. Pediatrics (2007); 120 (4):e1051-e1058.

-

Din Z et al. PEDIATRICS 2013; Volume 131, Number 3.

-

Joosten K and Meyer R. EJCN (2010) 64, S22–S24.

-

WHO/FAO/UNU Report of a Joint Expert Consultation. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition. Technical Report Series No. 935. World Health Organisation 2007;185–193.

-

Billeaud C, Guillet J, Sandler B. Eur J ClinNutr 1990; 44 (8): 577-83.

-

NHS Choices. Types of formula milk. (2016). Available here. Accessed October 2018.

-

HSE, 2007. Available here. Accessed October 2018

-

Carnielli VP et al. AJCN (1995b): 62: 776–81.

-

Carnielli VP et al. JPGN (1996);23(5): 553-60.

-

Lucas et al. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (1997);77: F178-184.

-

Kennedy K et al. Am J ClinNutr 1999;70:920–7